Framing the Project

Congratulations! You’ve selected your nonprofit project and are ready to get started. Before you crack open your IDE and dive into the code, the first few hours of the jam are most well spent building a deep understanding of the problem your nonprofit is trying to solve. By doing this well, you will have a better defined path for the next 40+ hours. You may also discover unexpected solutions that your nonprofit didn’t even know to ask for. After all, they are experts in serving their communities, not the nuances of the latest and greatest technology.

Interviewing Your Nonprofit

Take (Post It) Notes

A lot is about to be said in the next hour. You cannot possibly remember it all. You also don’t know enough yet to understand how what they are saying this moment connects to an insight you’ll have in two hours. Your first instinct may be to do this in a notebook or shared document, but the following “low tech” approach has a number of benefits.

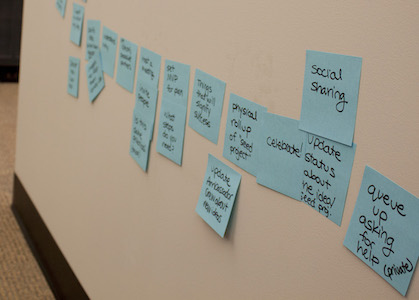

PostIt Notes have become almost synonymous with brainstorming & creativity for good reason. They are flexible, tangible, collaborative, and low tech (no account setup required; not even a computer!). By taking notes on PostIts, you can quickly connect and organize ideas in a way that both your team and nonprofits can quickly see and contribute to. Jot one idea per note. Come up with a loose color coding (like blue for notes, yellow for ideas, red for pain points, or you’re fine just sticking to one color if it is too much to keep track of). Don’t worry too much about organizing them at first or people writing the same thing on different notes. You can start by putting them randomly on a wall or even a table. Once the ideas are out there, you can start grouping them. Stick related notes to one another so you can move the group all together.

Active & Open Listening

The focus of this time is to hear what they have to say, not to try to push your own solution or ideas (wait for it, that can come later). By using active listening and open interview questions, you’ll get much richer information.

-

Pay attention. This is not the time to be setting up your laptop or researching your preferred solution.

-

Repeat, reframe & summarize what you’re hearing. “So you’re saying it would be helpful to… Did I get that right?”

-

Ask questions to clarify & get below the surface. “What do you mean when you say…” “I heard you say… Tell me more about that.”

-

Let them talk. Try to avoid talking much beyond your questions. Don’t interrupt and be ok with some silence after your questions.

-

Dig into the why. Anytime they veer into proposing solutions, dig deeper. “You say you need an app. Why?” “Tell me more about how X would change things.” The technique of “5 Whys” can surface an underlying need that may have simpler solutions than what they realize.

-

Start broad, get more specific.

-

Ask for examples of the problem they’re trying to solve. Get specific. “The last time” or “the worst time” is usually much more detailed than the general average version of the story.

Example Interview Questions

- How did you come to work at this nonprofit?

- What is your nonprofit’s mission? What is its business model?

- How do you measure your success?

- What keeps you up at night? Why?

- Tell us about the community you serve.

- How does your nonprofit relate to other branches/regions? (If they are part of a larger organization.)

- How did you come up with your idea?

- How does this solution work today?

- How much time/money does it usually take?

- Do you expect this problem to improve, worsen or stay the same in the upcoming year? Why?

- What is the most frustrating thing about your current solution?

- What do you like/works well in the current solution?

- Tell me about the last time not having this project caused problems.

- What other solutions to this problem have you tried? What worked/didn’t work?

- Are there other challenges you encounter when doing _____?

- What makes this challenge unique? Is this challenge faced by other branches/nonprofits?

- If others have similar problems, what do you like/not like about their solutions?

- How does this problem impact your staff, donors, volunteers, and community?

- What would it look like if this project was wildly successful?

- What would happen if nothing changed?

- What do you wish you could do that you can’t do today?

- What challenges or curve balls do you think we might hit?

- If we could only get one thing done this weekend, what should it be? Why?

Logistics Questions

- How often is content for this solution changing?

- Do they have a brand style guide? If they are part of a larger organization, they may have access to design colors, fonts, icons and photos that you can use to make your project accurately reflect their brand. If they don’t have one, there might be an opportunity to create one for them.

- What accounts & passwords to existing systems might be necessary? If they are asking to integrate into a current technology system, they should either create an account for you to log in or give you the credentials to log in. You’d hate to be making great progress at 2am only to be blocked by an unknown password.

- What’s the best way to contact them during the jam? Exchange cell numbers, email addresses or whatever their preferred means of communication.

- Do they have any budget for this project? Ideally try to use free solutions. However, sometimes you get what you pay for and there might be a great fit for a reasonable amount of money. Understand whether that is an option or not for your group.

- What is their plan for supporting this project after the jam? Who is going to be maintaining the content or process you are going to work on for the next 40+ hours? Understanding this plan can help you create good handover training and maintenance documentation (a great task for a non-technical teammate).

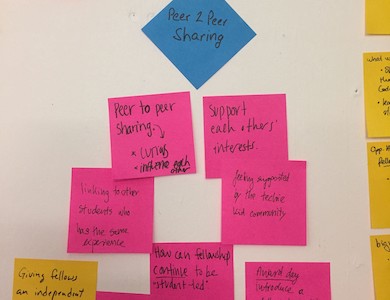

Understanding the Who

People are the heart of every nonprofit: staff, donors, volunteers, and the community they are serving. Each role will likely be impacted by your project differently or use it in different ways. Ask your nonprofits who the primary targets of this solution are. If they say everyone, try to get them to rank which groups are the most important audiences.

Have them help you build simple personas for the main audiences. This doesn’t have to be extensive or elaborate, but it will help anchor your project in the actual humans that will need to use it. You also may have multiple personas for one role if they have large enough differences. An example would be volunteers with different motivations or obstacles – a college student volunteer might have trouble coordinating transportation vs a retiree may have trouble navigating the website.

The main things you should define for each persona:

- Shorthand name (could be their role or a real name)

- Who are they (focus on the details that make a difference)

- What are their goals

- What are the current obstacles to those goals

Map Their Current Story

Instead of just talking about their current process, it is often helpful to see the story mapped out and then use it to plan out the ideal solution. Creating the map is a collaborative process, with both the nonprofit and team chipping in.

What Story Are You Telling

Since working with technology is an interactive experience, every interaction is a part of a story. Even an informational website has a story around it. If you’re feeling a bit stumped about where to start, start with the who. What is that persona trying to do and where do they start? For example, if the nonprofit has asked for a website to help their community see what services they offer, the story might be one of their community members seeking information about how to sign up for aid. How do they get this information today? Or if the nonprofit’s main pain with their current site is keeping it updated, you might map the process that a staff member has to take to update the content.

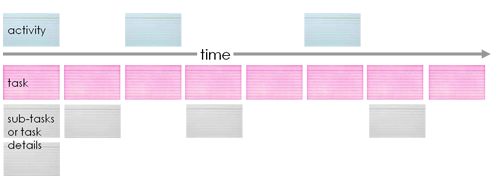

How to Make a Story Map

How the story map comes together will depend a lot on how your nonprofit chooses to tell their story. Sometimes you start broad and get more specific. Other times they may get really detailed from the start and you’ll need to add the top summaries later. Each PostIt should have only one thing on it, and generally you should start what’s on the PostIt start with a verb (i.e. “Sign Up for Newsletter,” “Browse Events”). Also give yourself plenty of space. You will probably be coming back and adding elements or moving things around as you progress.

The top row is the most general. If you were to describe an evening routine it might look something like “Dinner,” “Cleanup,” “Relax” (or other things you do), “Get Ready for Bed,” “Sleep.” If your story involves more than one persona, include a note with which persona(s) do this activity.

The next row are the tasks, going from left to right with time. This row should stay pretty high level still. For example, in the “Dinner” activity above, you may have “Prepare Food,” “Set Table,” “Serve Food,” “Eat.” In a different color, the specifics of how you do each of those things can then be spelled out below in the sub-tasks. It is easier to move later if you stick the sub steps PostIts on one another instead of the wall, so you can move them as a big group.

Using a different color (often red), write down the biggest pain points with this current state. You may start to see themes emerging with specific steps being far more painful than others.

Form a Problem Statement

At this point you have enough information to form your problem statement. One way of framing this is in a question:

How might we [Insert Problem] (optionally add: so that [Desired Outcome])?

Example from 2019 DSMHack

Original solution idea from nonprofit: Build a volunteer rewards store.

Reframed problem statement: How might we encourage volunteers to volunteer again after an initial organized volunteering event?

In the initial conversations the team discovered that there were also problems with their sign up forms that made it difficult to see upcoming events. The team delivered the asked-for rewards store AND improved their volunteer sign up forms to better solve the problem from multiple angles.

Map the Solution

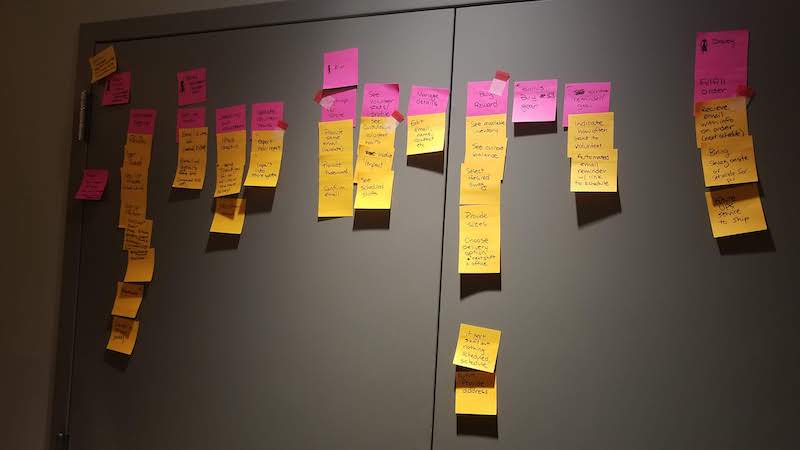

Now you can move on to the ideal state story map. You can decide if it should be a different color on the existing map (good if you aren’t changing much about the current process), or a completely new map. Be sure to go end to end and cover the entire process. For an app, be sure to consider all the CRUD (create, read, update, delete) actions. You want to end up with at a summary of all the work you’re going to be taking on in the jam.

Double check that the solution actually addresses the main pain points you noted in the current story. If not, you might want to quickly brainstorm with your nonprofit other ideas that might better solve some of the pains they have expressed.

This is an example map, from the 2019 DSMHack, mapping the process of volunteers signing up through showing up for their shift. The red flags became the basis for planning the specific work items to be divided up and completed during the jam.

Prioritize & Go

Now that you have a clear picture of their current problems and goal for the solution, you can better plan out the work ahead of you. Looking at the your solution story map, star or flag the sub-steps that form most essential pieces for the persona to accomplish their goal (the red flags on the example above). This will form the heart of work that you can divide up amongst the team and knock out in the next 40+ hours. Other sub-steps then can be additional work to get to if you have time.

You can now move or rewrite the sub-steps you want to focus on to a Kanban Board and get hacking!